These life stories may contain descriptions of childhood trauma and abuse, as well as images, voices and names of people now deceased. If you need help, you can find contact details for some relevant support services on our support page.

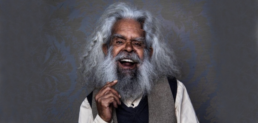

Respected Indigenous elder and widely loved Australian actor and activist, Uncle Jack Charles (1943-2022), spent his childhood in institutions and foster care as a member of the Stolen Generations.

Charles, a Bunurong, Dja Dja Wurrung, Woiwurrung and Yorta Yorta man, was born in Carlton, Victoria. He was one of thirteen children born to Bunurong woman Blanche Charles. Anticipating that her baby would be stolen at birth, Blanche escaped from authorities by hiding in an Aboriginal camp near Shepparton. But at four months old, Charles was stolen from his mother and assigned a criminal record as a ward of the state.

My first offence … was as an Aboriginal boy, four months old, child in need of care and attention (King, 2022).

At the age of two Charles was placed at Box Hill Boys’ Home, which was run by the Salvation Army and the subject of nine submissions to the Inquiry into Children in Institutional Care. Over the next twelve years Charles was physically and sexually abused by staff and other boys. He was also denied any knowledge of, or connections to, his family and culture.

At age fourteen Charles was placed in a foster home with an abusive woman who lied to him about his past and prevented him from reconnecting with his mother. Charles was searching for his mother the night he was arrested for the first time at age sixteen.

Charles was struggling with substance abuse and in and out of prison by the time he connected with his mother at age eighteen. During the three decades that followed, he often slept rough and was incarcerated twenty-one times for charges related to heroin addiction and burglary.

Charles then went on to become the self-proclaimed ‘Granddaddy of Indigenous theatre’. In 1971, he and Bob Mazza co-founded Australia’s first Indigenous-controlled theatre company, Nindethana, which means ‘place for a corroboree’. Charles performed widely in television, film and live theatre throughout Australia and in New Zealand, United States, Ireland, and Japan.

Highlights of Charles’ Australian television career include Ben Hall (1975), Rush (1976), Problems (2012), Black Comedy (2014-2020), The Gods of Wheat Street (2016), Cleverman (2016-2017), Wolf Creek (2016), Play School (2017) and Preppers (2021). The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith (1978). Blackfellas (1993), and Pan (2015) are some of his notable feature film credits.

Charles was perhaps best known for sharing First Nations culture and storytelling within mainstream audiences both nationally and internationally. He was passionate about promoting ‘the Blak arts’ to encourage understanding, healing, and reconciliation.

So I’m rapped today that so much is being handed to white Australia, to all Australians, by the tenacity and the valiant effort of theatre practitioners, filmmakers, writers, poets, dancers, people in the Blak arts, even young rappers. They’re telling their stories. We’re being re-educated, and it’s about time (Butler, 2021).

According to Charles’ lifelong friend, theatre director Rachael Maza, one of his greatest strengths was engaging and educating non-Indigenous audiences about the impacts of the Stolen Generations.

People understood for the first time in a really deep way, what that lived experience was of being a stolen Gen person… when you come along and you meet Uncle Jack and you hear his story, they got it. They got it in such a deep, profound way (Cross, 2022).

Charles’ award-winning auto-biographical show, Jack Charles V The Crown, debuted at the Ilbijerri theatre in 2010. He described his life as a gay Indigenous man in a second autobiographical show, A Night with Jack Charles (2019). His memoir, Jack Charles: Born-Again Blakfella, was published by Penguin books in 2020. Charles’ final role as the voice of the advertising campaigns for the AFL’s 2022 final series attests to his popularity among Australians of many backgrounds.

Charles’ activist career began as a mentor to fellow prisoners while incarcerated as a young man. Later in life, he regularly visited young inmates in prisons and detention centres, arguing that “who better to talk to these men, then someone who understands all too well their experience” (ACA). Charles connected with countless inmates who he explained would “thank me for hearing my journey, because I let them know they have nothing to be ashamed of,” (Wade, 2019).

Charles was a dedicated campaigner against injustices, most notably the over-representation of Indigenous people in the prison system. He also used his platform as a well-known actor and highly-respected elder to give voice to broader needs within Indigenous communities, explaining:

Sometimes the government needs direction from elders with lived experience who can see a way forward to address the systemic issues that are confounding us and putting us behind the eight ball (Wade, 2019).

Charles teamed up with Indigenous actor Ernie Dingo to promote the Raise the Age campaign aimed at increasing the age of criminal responsibility to keep Indigenous children as young as ten years old out of jail. He also promoted recognition of ‘cross-over youth’ who are Indigenous, LGBTIQ+, and involved in juvenile justice. Charles emphasised, “Us gay and Indigenous mob, we’re fringe dwellers twice over” but that this identity is “what gives us great strength,” (Wade, 2019).

Charles petitioned the office of Victorian Premier Daniel Andrews to fund further development of Indigenous community centres, explaining:

We need an injection of serious funding to buy our own buildings to use for community centres… An Indigenous community centre is an establishment, a sanctuary for Aboriginal people where the community can get together and talk about our personal issues with each other… it’s the only way forward (Wade, 2019).

Charles’ final contribution to Care Leaver activism was speaking in 2022 at the Yoorrook Justice Commission as part of the “first formal truth-telling process into injustices experienced by First Peoples in Victoria.” Charles described how he was stolen from his mother as a baby, then sexually abused and racially vilified while in State ‘care’.

Charles received accolades for his many contributions to arts and activism. His lifetime contribution to Indigenous media was recognised with a Tudawali Award at the Message Sticks Festival in 2009. In 2014 he was the first Indigenous recipient of a Green Room Lifetime Achievement Award for contributions to theatre, and then became a Patron of the Association in 2021. Charles was the 2016 Victorian Senior Australian of the Year. In 2019 he received a Red Ochre lifetime achievement award by the Australian Council of the Arts. Finally, he was honoured as the National NAIDOC Week Awards 2022 Male Elder of the Year.

Charles’ forced separation from family as a member of the Stolen Generations was the subject of a 2021 episode of the Australian television programme Who Do You Think You Are. Charles describes how he tracked down five of his eleven living siblings and learned his mother was still alive but had no information about his father. The programme helped him identify his father as Hilton Hamilton Walsh, a ‘snappy dressing’ Yorta Yorta man. The two never had the chance to meet.

Charles passed away on 13 September 2022 at the age of seventy-nine after suffering a stroke. He was surrounded by loved ones at Royal Melbourne Hospital. His family family have given permission to use his name and images after his death.

Uncle Jack Charles was honoured in a State Funeral held on 18 October 2022. It was open to the public and live streamed in Victorian prisons, remand centres and youth justice centres in recognition of his prison reform activism.

Charles’ is remembered as “a colourful character, a master orator and a driving force helping everyone who calls Australia home understand our shared history, our trauma and our opportunity,” (Smith, 2022). Statements from politicians honour his legacy.

Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese stated:

He was a great character and what a tough life. He was someone taken from his mum, part of the Stolen Generations, enormous trouble with the law but he had a background not just of that but of abuse as a young boy. As someone who came through that to be a person of hope, he was someone who was a promoter of reconciliation and bringing the country together. (Nunn, 2022).

According to Victorian Premier Daniel Andrews:

There is no actor, no activist, no survivor and no Victorian quite like Uncle Jack Charles. He leaves behind a legacy – one of profound honesty, survival and reconciliation – and one that every single Victorian can be proud of. (NIT, 2022)

Finally, Federal Indigenous Australians Minister Linda Burney summarised:

The beauty of Uncle Jack Charles is that he never put himself above anybody. His success was everyone’s success. He was funny, he was humble, and he used his life as an example to others of what’s possible now. (Smith, 2022)

References

“Box Hill Boys’ Home (1913 - 1984)”, Find and Connect, 2022. https://www.findandconnect.gov.au/guide/vic/E000258

Butler, Dan. “Uncle Jack Charles on Blak art’s educating power.” SBS/NITV, 12 Dec 2021. https://www.sbs.com.au/nitv/article/uncle-jack-charles-on-blak-arts-educating-power/rlc88thup

Cross, Jared. “Even in his final moments, Uncle Jack Charles ‘remained a resilient, charming’ man.” National Indigenous Times, 20 September 2022. https://www.nit.com.au/even-in-his-final-moments-uncle-jack-charles-remained-a-resilient-charming-man/

Lunn, Stephen. “Charles, Jack (1943–2022)”, Obituaries Australia, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, 13 September 2022. https://ia.anu.edu.au/biography/charles-jack-32787/text40778

King, Jennifer. “Uncle Jack Charles: the ‘lost boy’ who found his way through storytelling.” The Guardian, 13 September 2022. https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2022/sep/13/uncle-jack-charles-the-lost-boy-who-found-his-way-through-storytelling

Smith, Tamati. “Reflecting on the remarkable, painful and inspiring life of Uncle Jack Charles.” National Indigenous Times, 27 Sept 2022. https://www.nit.com.au/reflecting-on-the-remarkable-painful-and-inspiring-life-of-uncle-jack-charles/

Wade, Matthew. “Uncle Jack Charles on Helping Incarcerated Indigenous Youth- Gay and Straight Alike.” Star Observer, 27 March 2019. https://www.starobserver.com.au/news/national-news/uncle-jack-charles-on-indigenous-community-centres-and-helping-incarcerated-youth/179989

“Uncle Jack Charles, Red Ochre Award, 2019.” Australia Council for the Arts. https://australiacouncil.gov.au/news/biographies/uncle-jack-charles-red-ochre-award-2019/

“Victorian state funeral confirmed for Uncle Jack Charles.” National Indigenous Times, 26 September 2022. https://www.nit.com.au/victorian-state-funeral-confirmed-for-uncle-jack-charles/

Image available here.