These life stories may contain descriptions of childhood trauma and abuse, as well as images, voices and names of people now deceased. If you need help, you can find contact details for some relevant support services on our support page.

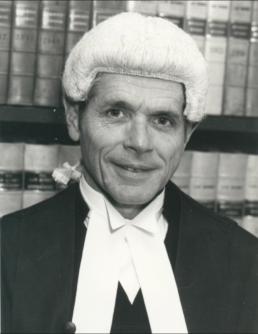

Ronald Darling Wilson (1922-2005), a prominent human rights activist and the 28th Justice of the High Court of Australia, was in kinship care as a child.

Wilson was the second son born into a privileged family in Geraldton, Western Australia. His father was a solicitor who had migrated from England to Australia in 1912. His mother was a homemaker who passed away when Wilson was four years old. From then on, Ronald and his older brother were looked after by a housekeeper. Wilson described the arrangement as that of a substitute caregiver who “for all practical purposes… was my mother” (ABC Radio, 2001).

When Wilson was seven years old his father suffered a debilitating stroke and spent the remaining five years of his life in hospice care. Wilson’s older brother, then fourteen years old, began caring for Wilson along with their housekeeper. Finances became tight without income from the law practice and the bank foreclosed on the family home in 1936. Before being forced to vacate, Wilson and his brother buried their father’s law library in the garden because it had no resale value in the post-Depression era.

The new household typically consisted of Wilson, his brother, the housekeeper, plus three to four additional young men at any given time. Wilson attended the local high school with these young men who contributed income towards living expenses as boarders. At the age of fourteen, he attained what was then known as the Junior Certificate. Wilson’s first job was as a messenger at the Geraldton Courthouse. He was promoted to the permanent public servant role of junior clerk on his fifteenth birthday.

In September 1941 Wilson enlisted in the army reserves. He then served in the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) and was deployed to England during WWII. Wilson had attained the rank of Flying Officer before being discharged from the military in 1946.

Wilson then began studying at the University of Western Australia and graduated with a Bachelor of Law degree in 1949. He was later awarded a prestigious Fulbright Scholarship to study a Master of Law degree from the University of Pennsylvania which he completed in 1957.

After his return to Western Australia, Wilson became the state’s crown prosecutor in 1959. In 1963 he attained the status of Queen’s Council, a title associated with the highest level of professional recognition as a barrister. In 1969, he began a ten-year term as the Western Australia Solicitor-General.

In 1979 Wilson became the first Western Australian to be appointed to the High Court of Australia, a position which provided a government vehicle and chauffeur. However, Wilson chose to continue driving his second-hand Corolla while serving as a High Court Justice, a testament to his personal character.

“Sir Ronald Wilson never promoted himself, never sought public attention, believed he was hard working, but not exceptional… His commitment to the values of human rights, equality, fairness, playing his part in the Native Title cases, bringing the plight of the Stolen Generation[s] to national attention, and many other commitments is inspiring” (Cannon, 2018).

Wilson retired from the bench in 1989 shortly after being elected as the first non-ordained national president of the Uniting Church of Australia, where he was influential in promoting social justice. He also served as Chancellor of Murdoch University between 1980 to 1995. Wilson began a seven-year term as president of the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission (HREOC) in 1990. In 1991 he became Deputy Chairman of the Council for Aboriginal Reconciliation and president of the Australian Branch of the World Conference on Religion and Peace.

Wilson was a highly committed human rights campaigner whose most notable achievement was in collaboration with Mick Dodson, the Australian Human Rights Commission’s first Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice commissioner. The pair conducted a landmark Inquiry into the removal of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children from their families summarised in the 1997 ‘Bringing them Home’ report.

According to Mick Dodson, “Once you convince Ron Wilson you can have no one more passionate as an advocate,” (Cannon, 2018).

The ‘Bringing them Home’ report included the stories of Indigenous Australians affected by Stolen Generations policies, and its recommendations were aimed at healing and reconciliation. Wilson continued to travel the country after the report’s release to support campaigners and others who gave evidence to the Inquiry. The Howard Government rejected the report and ignored both the grassroots Sorry movement and Wilson’s repeated requests for a formal governmental apology for wrongs committed against generations of Indigenous Australians.

During and after the Inquiry, Wilson “copped tremendous and unjust criticism for his role in telling the truth they [the government] did not want to hear,” according to former president of the Uniting Church, Reverend Dean Drayton (SMH, 2005). Eleven years after the release of the Report, a formal National Apology was delivered by the subsequent Prime Minister Kevin Rudd in February 2008.

Sir Ronald Darling Wilson died in Perth at the age of eighty-three on 15 July 2005. His life was commemorated by the now deceased former national chairman of the Uniting Church and Aboriginal Christian Congress, Reverend Sealin Garlett,

“Those of us privileged to know Sir Ron knew about his deep concern for Indigenous Australia. [He] was a small man in stature but he had a big heart,” (SMH, 2005).

A statement from the then-president of the Australian Human Rights Commission, John von Doussa QC, described the Bringing Them Home Report as one of Sir Ronald Darling Wilson’s “greatest legacies and will continue to be the subject of public debate about how this sorry part of our history will impact on Indigenous people for a long time in the future,” (AHRC, 2005).

Sir Ronald Darling Wilson was the recipient of many honours and awards, including being appointed a Companion of the Order of St Michael and St George in 1978, a Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire (KBE) in 1979 for services to law and human rights, a Companion of the Order of Australia (AC) in 1988, and a Centenary Medal in 2001. He and his wife, Lady Leila, had five children. He is remembered by his children as a caring and devoted father who attended their sports events and did the laundry.

References

Australian Human Rights Commission. “Tribute to Sir Ronald Wilson.” 18 July 2005. https://humanrights.gov.au/about/news/media-releases/tribute-sir-ronald-wilson

Adams, Phillip. “Australian Identity Sir Ronald Wilson.” ABC Radio National Late Night Live, August 9, 2001.

https://www.abc.net.au/rn/features/inbedwithphillip/episodes/204-sir-ronald-wilson/

Cannon, Paul Vincent. “A Quiet Integrity.” Parrallax, 5 June 2018. https://pvcann.com/tag/sir-ronald-wilson/

Durack, Peter. (2001). “Wilson, Ronald Darling”. In Blackshield, Tony; Coper, Michael; Williams, George. (eds.). The Oxford Companion to the High Court of Australia. The Oxford University Press Australia. pp 714-716. https://www.hcourt.gov.au/assets/justices/coper_hca_wilson.pdf

“Sir Ronald Wilson honoured by mourners.” Sydney Morning Herald, 23 July 2005.

https://www.smh.com.au/national/sir-ronald-wilson-honoured-by-mourners-20050723-gdlqh8.html

The University of Western Australia Historical Society. “Ronald Wilson (1922-2005)”.

https://www.web.uwa.edu.au/uwahs/uwa-ww2/stories/ronald-wilson

Image available here.