These life stories may contain descriptions of childhood trauma and abuse, as well as images, voices and names of people now deceased. If you need help, you can find contact details for some relevant support services on our support page.

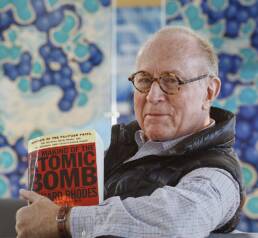

Pulitzer Prize-winning American historian, Richard Rhodes (b. 1937), was in kinship care, foster care and an institution as a child.

Richard Lee Rhodes was born in Kansas City. When he was thirteen months old, his mother, Georgia Saphronia Collier, killed herself.

Richard’s father, Arthur Rhodes, was left with three boys to care for. Relatives took the children in for a while, but Arthur ended up with Richard and Stanley (two years older than Richard), living in boarding houses from which he could go to work and the boys would be looked after in his absence. The oldest son, Mack, went to live with his paternal aunt in Washington State.

The Rhodes family lived in the one boarding house with the Gernhardt’s for about four years. After they left in 1944, they moved four times in two years with the boys going to three different schools during that time. Then, in February 1947, Richard, Stanley & Arthur moved into a boarding house with the woman who was to become Arthur’s second wife and the boys’ stepmother.

While Arthur was getting married and getting his new life organised, he sent Richard and Stanley to live with Gretta Schonmeier and her family for the summer. Rather than return home in August, as the boys were expecting, they stayed with the Schonmeier’s until October.

Dad sat us down with Anne, Aunt Anne…and told us nervously that they’d been married. That’s what the summer had been about. “We’re a whole family again,” Dad said.

“You can call me Mother now,” our father’s wife told us. She must have seen the look on our faces. Smiling a cold, triumphant smile. “Your dad’s let you run wild,” she said. “We’ll get along just fine just as soon as you two learn that we have a few rules around here” (Rhodes, 102).

Stanley and Richard only lived with “Aunt Anne” for twenty-eight months. Yet, for Richard, it felt like four years.

“Aunt Anne” was violent, exploitative and controlling. She beat the boys, sent them out door to door selling and kept the money they made, and prevented Richard from going to the toilet in the middle of the night, leaving him to devise other ways of not wetting the bed.

Slapping us, kicking us, bashing our heads with a broom handle or a mop or the stiletto heel of a shoe, slashing our backs and the backs of our legs with the buckle of a belt, our step mother exerted one kind of control over us, battery that was immediately coercive but intermittent and limited in effect…More effective control required undermining our boundaries more sharply. More effective control required undermining our boundaries from within…The techniques she developed led eventually to a full-scale assault (Rhodes, 117).

For two years, to discipline us, to punish us and to maximize her profits from our labor, our stepmother not only beat us but also systematically starved us. Dad let it happen, protesting when he dared but too intimidated to protect us. He made his own life easier at the expense of ours. I’ve never forgiven him for that and never will (Rhodes, 128).

The torture stopped when Stanley went to the police station and reported the abuse at home. Stanley spent two weeks in a juvenile detention centre before the case went to court; then the boys were taken to the Drumm Institute. Life at Drumm was better for Richard. There was plenty of food, skills to learn, safety, and beautiful surroundings. All boys at Drumm contributed to the running of the place including growing most of their own food.

In his final of six years at Drumm, Richard was encouraged to apply to Yale University. When he gained admittance he was also awarded a Victor Wilson Scholarship which covered tuition fees and living expenses. Richard was mentored by the Chair of the Victor Wilson committee for four years.

Jay and his wife…made a home for me on their farm between my graduation from Drumm and my departure in September for New Haven. Jay needed a hired hand, but he also wanted to be sure I knew which fork to use. He sent me to his tailor. For four years he saw to it that my scholarship was renewed…The Olanders served as surrogate parents until I finished school. Later we lost touch. This is a good place to thank them, publicly, for all they did for me (Rhodes, 264).

Richard Rhodes began writing “seriously” in his thirties. He has gone on to publish 26 fiction and non-fiction books, including the Pulitzer Prize-winning The Making of the Atomic Bomb (1987). During 2023, Richard Rhodes’ opinion of the film Oppenheimer (2023) – the biographical film of theoretical physicist Robert Oppenheimer who was the director of Manhattan Project’s Los Alamos Laboratory – has been much canvassed given Rhodes’ considerable knowledge of Oppenheimer and the Manhattan Project.

Rhodes’ memoir, A Hole in the World: An American Boyhood (1990), was in the vanguard of a new genre of writing, memoirs reporting on child abuse. The book elicited a considerable response, including from orphanage survivors interviewed by Rhodes and his partner, Ginger Rhodes, for their follow-up book, Trying to Get Some Dignity (1996).

Half of the proceeds of The Hole in the World went to enable Stanley Rhodes to finish his university education. Stanley served time in prison because he was a conscientious objector to the Korean War. He later became a specialist welder with a shop in Los Angeles, but what he really wanted to do was go back to college.

He squeezed three years of classes into two and graduated at fifty-eight from the University of Idaho, where he’d been working as a janitor. Mack and I and our families converged on the campus to see him graduate. As the dean handed him his diploma, he popped off his mortarboard, popped on his JANITOR work cap, and walked proudly down the stage (280).

References:

Banks, Russell. “The Abuse Had to Stop.” The New York Times, 28 October 1990. https://www.nytimes.com/1990/10/28/books/the-abuse-had-to-stop.html

Richard Rhodes website. https://www.richardrhodes.net/

Rhodes, Richard. A Hole in the World: An American Boyhood. University Press of Kansas, 1990.

Image available here.