These life stories may contain descriptions of childhood trauma and abuse, as well as images, voices and names of people now deceased. If you need help, you can find contact details for some relevant support services on our support page.

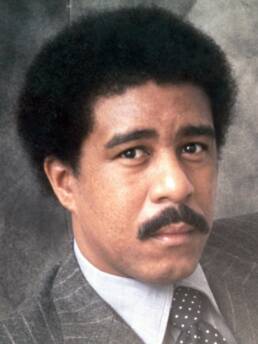

African American comedian and actor, Richard Pryor (1940-2005), was in kinship care as a child.

Richard Franklin Lennox Thomas Pryor was born in Peoria, a small town in central Illinois. His mother, Gertrude, was a sex worker in his grandmother’s brothel, and his father, Leroy (also known as Buck Carter), was a former boxer who solicited clients for the brothel.

Richard’s church-going grandmother, Marie Pryor, was an enterprising woman who, by 1947, ran two brothels, a nightclub, and a pub in Peoria; she had moved there in 1930. Marie later added other businesses to her portfolio, including a restaurant.

When Richard was five, Gertrude fled her husband’s violence and returned to her family home in Springfield, the capital city of Illinois. She filed for divorce from Leroy, but the judge awarded custody of Richard to his father.

There was a period in 1948 when young Richard lived with his mother and her family on a farm on the outskirts of Springfield. For Richard, this was a “slice of heaven” (Saul 51), a short-lived reprieve from the bullying Richard suffered back in Peoria from “boys who hailed from the valley’s white protestant blue-collar families” (Saul 51),

They ganged up on him in the vacant lot across from the school, sometimes giving him flimsy grounds for their attack, often not. Slight in stature, Richard fought back most impressively with his mouth. Bottled up tight at home, elsewhere he was loose, and mimicking the kind of salty talk he heard at Marie’s brothel and the Famous Door [tavern] (Saul 51).

At school again in Peoria, Richard struggled with low grades and with being punished for being mischievous. But in testing the classroom boundaries, he also discovered a talent for entertaining his classmates with hastily constructed excuses for his bad behaviour.

Richard often skipped classes too and engaged in a rich fantasy life in his bedroom.

He listened to his grandmother’s Doris Day records and confected a Doris Day scenario in his mind… “I’d write a lot,” he remembered, “I’d lock myself up in my room for two or three days at a time without eating or sleeping, just writing about life” (Saul 54-55).

Even when Richard was living with his father and grandmother in one household, Marie was the principal parental figure. He called her Mama and she…

… ran Richard like she ran her brothels, with a stiff sense of right and wrong and an equally stiff sense of possessiveness. Sometimes she hurt Richard physically, whipping him with birch switches or slamming him with an iron skillet. But she also gave him a sense of dignity, a bottom-dog wisdom (Saul, Digital companion).

Buck’s new wife, Viola—they married in 1950—was kind to Richard, a relief for him after the harshness of Marie and the unpredictable violence of Buck. Viola tried to instil her Catholic values in the boy and enrolled him in a Catholic school. The promised ‘fresh start’ was over when parents complained about how Richard’s family earned their living.

In 1952, Richard moved with his grandmother to a new area, one where there were few black people. Enrolled in a “nearly all-white elementary school” Richard “struggled to find his place” (Saul, Digital companion). Yet there was a teacher, a Mrs Margaret Yingst, who felt sorry for Richard and reached an agreement with him: if Richard could get himself to school on time, he could entertain his classmates with a comedy routine for ten minutes on a Friday afternoon.

For his Friday-afternoon material, Richard borrowed liberally from the rubber-faced comedians of the day. He loved Red Skelton and Sid Caesar…and was especially inspired by Jerry Lewis. His comedy was solo slapstick, Lewis sans Martin. “Oh my, he could roll those eyes back,” remembered Yingst (Saul 60-61).

At the end of 1954, Richard left his grandmother’s home and moved in with his father. He was enrolled in Roosevelt Junior High where there was a more even mix of black and white students; it was “his sixth school in seven years” (Saul 66).

The following year, Richard began attending the Carver Center, a community centre where he met Juliette Whitaker, a drama teacher who encouraged the boy to play in Rumpelstiltskin. Performing well in the play, along with Whitaker’s encouragement, was a turning point for young Richard, who “became the Carver Center’s premier performer and began developing a reputation…The auditorium would be packed with kids waiting for Richard to come on for rehearsal (Tafoya 139).

After Richard was expelled from Central High in 1956—he had transferred to the nearly all-white school in September 1955—he did not return to complete his formal education. Instead, and at the behest of Buck, he did an assortment of low-paid jobs before he joined the Army in 1959. He served only sixteen months before he was discharged.

Pryor’s first regular comedy gig was at Harold Park’s club back in Peoria, and from there he began playing to mostly black audiences in clubs—known as the Blackbelt circuit—from St Louis to Youngstown in Ohio.

In 1962, Pryor went to New York and began working as a stand-up comedian, modeling himself on Bill Cosby. Conflicted at the lack of black people in his audiences and the need to not comment on this, Pryor left New York and went to Los Angeles where he recorded his first album which included sketches about his childhood and commentary on racism.

Even though Pryor, like so many comedians of his generation, began his career imitating Cosby, his act over the years would develop into something harder and harsher. Unlike Cosby’s, Pryor’s world is filled with dope dealers, addicts, prostitutes, street thugs, criminals, drunks, racists, and crazed spouses, and his language is the language of the brothels and pool halls in which he spent so much of his youth (Tafoya 136).

From 1972 to 1975, Richard Pryor had a successful career in Hollywood, co-writing films such as The Mack (1973) and Blazing Saddles (1974) and working with Lily Tomlin on her television shows. His recording career was also successful, particularly after That Nigger’s Crazy was released in 1974. By 1975 Pryor was regarded by many as “the funniest person on the planet” and his 1979 film, Richard Pryor Live in Concert, grossed $20 million (Saul, Digital Companion).

In September 1977, the Save Our Human Rights Foundation, a San Francisco-based group of gay rights activists, held a benefit concert at the Hollywood Bowl in response to celebrity Anita Bryant’s attacks against the gay community. Dismayed at the under-representation of African Americans on stage and in the audience, Pryor famously challenged what he saw as racism in the gay community.

By 1980, Richard Pryor was struggling with his public success and private pain and, on 9 June that year, he set himself on fire. When he recovered, Pryor continued to make films, but most were of a lower standard than earlier ones.

During the decades after Pryor was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis in 1986, he lived a more quiet, less public life. He died of a heart attack on 10 December 2005.

Richard Pryor’s impact on American comedy is regarded as substantial: he broke down many barriers, influenced future comedians such as Chris Rock and Eddie Murphy, and:

In addition to superb storytelling, exquisite timing, and stellar material, Pryor was able to take intimacy and honesty to unprecedented levels and through his act-outs was able to provide voices for the voiceless (Tafoya 169).

References:

Saul, Scott. Becoming Richard Pryor. New York: Harper Collins Publishers, 2014.

Saul, Scott. “Richard Pryor’s Peoria”. A Digital companion to the biography Becoming Richard Pryor. https://www.becomingrichardpryor.com/pryors-peoria/

Saul, Scott. “Richard Pryor: meltdown at the Hollywood Bowl.” The Guardian, 12 January 2015. https://www.theguardian.com/stage/2015/jan/11/richard-pryor-great-meltdown-racist-hollywood-bowl

Tafoya, Eddie. Icons of African American comedy. Santa Barbara, Calif: Greenwood, 2011.

Image from here