These life stories may contain descriptions of childhood trauma and abuse, as well as images, voices and names of people now deceased. If you need help, you can find contact details for some relevant support services on our support page.

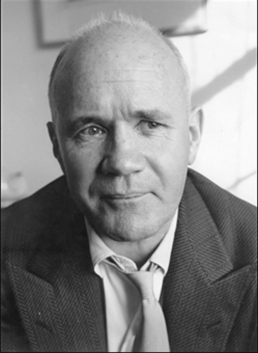

Pioneering French writer, Jean Genet (1910-1986), was in a foundling home, foster care and a reform school.

Jean Genet was born ‘illegitimate’ in Paris, France to twenty-two year old Gabrielle Genet who abandoned him to a foundling home when he was about seven months old. Genet remained a ward of the state until he was twenty-one.

Jean was put into foster care with a rural working-class family in the Morvan region (it is not clear at what age, some sources say when he was seven). He began stealing at the age of ten.

When he stole some money from his foster mother’s purse, she called him a ”little thief” and, as Genet told the story, from then on he lived out that role and whatever role that was imposed on him (Gussow).

Jean was fifteen when he was sent to the notorious reform school, Mettray.

“… fist fights, often fatal, that wardens interfere with; dormitory hammocks; silences during work and mealtimes, ridiculously pronounced prayers, barracks punishments; clogs; burned feet; military marches under the noontime sun; mess kits of cold water; and so on. We experienced it all at Mettray… “(Genet cited by Gray).

His experiences in the institution are recounted in his 1945 novel Miracle of the Rose.

According to Genet, he escaped Mettray when he was twenty-one, joined and left the French Foreign Legion, and then led a nomadic life across Europe, including in Nazi Germany which he characterised as a “nation of thieves” (Genet cited by Gussow). His autobiographical The Thief’s Journal (1949) gives a detailed account of his experiences:

The Thief’s Journal [is Genet’s] most exquisite piece of autobiographical fiction. He is the transparent observer reclaiming the suffering and exhilaration of his own follies, trials, and evolution. There are no masks; there are veils. He does not retreat; he extracts the noble of the ignoble (Smith).

Genet was in and out of prison nine times. It was in prison that he began writing; he wrote his first novel Our Lady of the Flowers (1943) while incarcerated in Fresnes in 1942.

Jean came to the attention of influential French artist and poet Jean Cocteau and was later mentored by philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre.

Jean Cocteau, in the early 40’s, was to inauguate Genet’s public career just as, a few years later, Sartre would consecrate it. After a number of stays in France’s most notorious prisons for repeated thefts, Genet had become a strange hybrid: half criminal and half literary celebrity (de Courtivron).

In 1948 Genet was found guilty of theft for the tenth time and faced automatic life imprisonment if convicted again. He was granted a pardon in advance by the president of the French republic largely due to appeals made on his behalf made by Cocteau and Sartre.

Genet went on to write numerous notable novels and plays. The Times (London) described Genet as “the most original and provocative writer of his generation.”

References:

de Courtivron, Isabelle. “The High Priest of Apostasy.” The New York Times, 7 November 1993. https://archive.nytimes.com/www.nytimes.com/books/97/09/14/reviews/16319.html

“Jean Genet.” Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Jean-Genet

“Jean Genet.” Grove Atlantic. https://groveatlantic.com/author/jean-genet/

Gray, John. “The crimes of Jean Genet.” The New Statesman, 11 December 2019. https://www.newstatesman.com/culture/2019/12/the-crimes-of-jean-genet

Gussow, Mel. “Jean Genet, The Playwright, Dies at 75.” The New York Times, 16 April 1986. https://www.nytimes.com/1986/04/16/obituaries/jean-genet-the-playwright-dies-at-75.html

Smith, Patti. “Holy Disobedience: On Jean Genet’s The Thief’s Journal.” The Paris Review, 13 August 2018. https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2018/08/13/holy-disobedience-on-jean-genets-the-thiefs-journal/

Image available here.