These life stories may contain descriptions of childhood trauma and abuse, as well as images, voices and names of people now deceased. If you need help, you can find contact details for some relevant support services on our support page.

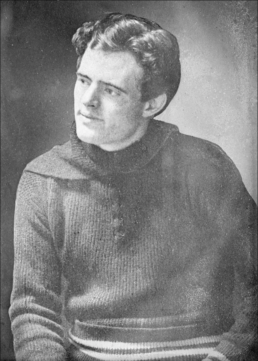

American writer Jack London (1876-1916) was in foster care as a baby.

John Griffith London was born in San Francisco, California to unmarried Flora Wellman who had been abandoned by her partner, William Henry Chaney. Chaney is likely to have been John’s father. Flora married John London in 1876, and Jack London grew up – in Oakland, California – thinking John was his biological father.

Flora was too ill to care for baby Jack and the infant was placed into foster care at around eight months of age with former slave, Virginia “Jenny” Prentice. Jenny had recently lost a baby and she cared for Jack until he was about twenty-four months of age. Jack remained in contact with Jenny Prentice for the rest of his life.

Jack had a difficult relationship with Flora and he was under pressure from an early age to contribute to the family income:

“Duty – at 10 years old I was on the streets selling newspapers. Every cent was turned over to my people, and I went to school in constant shame of the hats, shoes, clothes I wore. Duty – from then on I had no childhood. Up at three o’clock in the morning to carry papers. When that was finished I did not go home but continued on to school. School out, my evening papers. Saturday I worked on an ice wagon. Sunday I went to a bowling alley and set up pins for drunken Dutchmen. Duty – I turned over every cent and went dressed like a scarecrow” (London cited by Stefoff, 22).

Jack left school at the mandatory leaving age of thirteen and did a range of precarious working-class jobs, including becoming an oyster pirate and working in a pickle cannery when he was fifteen. The latter he described in John Barleycorn (1913).

In 1893, Flora drew Jack’s attention to a competition for “articles by writers under 22 years old” (Stefoff, 36) in the local paper and encouraged him to enter. His essay, ‘Story of a Typhoon off the Coast of Japan’, was printed on 12 November 1893.

Jack London spent thirty days in prison for vagrancy while on the road in Buffalo, an important formative experience as the injustice – summarily sentenced without the opportunity to speak to a lawyer – and the brutality he witnessed influenced his commitment to social justice.

The experience also meant Jack decided he needed to fit into society, rather than live on the margins of it. He never wanted to risk imprisonment again, and nor did he want to continue with manual work.

Jack returned to Oakland in 1894 and enrolled in high school. Although he felt out of place as a nineteen-year-old with considerable life experience amongst fifteen-year-olds with little, the school newspaper published a number of his essays and stories, he learned much from joining the Henry Clay Debating Society, and he was back hanging out at the Oakland Public Library.

He then went on to the University of California in 1896 but was disappointed with his brief time there. He felt out of place amongst the young middle-class students and his classes did not excite him in the way the debating society and the socialist movement (he had signed on with the Oakland branch of the Socialist Labor Party in 1896) had. Instead of completing his degree, Jack went travelling again, this time to the Klondike in Canada and then on to Alaska.

Back home in Oakland, Jack studied books about writing and writers, sent out myriad stories and essays to magazine editors, and learned from the notes on the many rejection slips he received. Finally, he sold a story to the Overland Monthly in December 1898. A year later he was earning his living by writing, and soon he was being commissioned to write pieces.

After the Call of the Wild (1903) became a bestseller, Jack London became a celebrity.

Jack London married for the second time in 1905 after his divorce from Bess Maddern (to whom he was married in 1900). Charmian Kitteridge (1871-1955) had grown up in kinship care and from her uncle Rosceo Eames learned stenography and typing, paid her way through two years of university working as secretary to Susan Mills, co-founder of Mills College, and supported herself as an office worker after she dropped out of university.

Charmain became Jack London’s secretary and after his death, devoted herself to maintaining his popularity. She travelled across America and to Europe promoting his work, sold his writing to Hollywood, and became a public figure in her own right as she gave talks about London.

Few writers of the early 20th century were more popular than Jack London, or more controversial. His personality and his work both made strong impressions on all who encountered them. People either loved London and his writing or scorned them – there was no middle ground. Even after died he continued to arouse strong feelings…Many scholars came to regard London…as a minor writer of little lasting importance…At the same time, however, some of his best and most beloved books and stories…quietly became classics (Stefoff, 8-9).

References:

Barltrop, Robert. Jack London: The Man, the Writer, the Rebel. London: Pluto Press, 1976.

Campbell, Donna. “Fictionalizing Jack London. Charmian London and Rose Wilder Lane as Biographers.” Studies in American Naturalism, vol. 7 (2012): pp 176-192.

“Jack London”. Britannica, 2021. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Jack-London

Kershaw, Alex. Jack London. A Life. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1997.

Stasz, Clarice. Jack London’s Women. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2001.

Stefoff, Rebecca. Jack London: An American Original. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002.

Image available here.