These stories may contain descriptions of childhood trauma and abuse. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people should be aware that this website may contain images, voices or names of people who may have passed away. If you need help, you can find contact details for some relevant services on our support page.

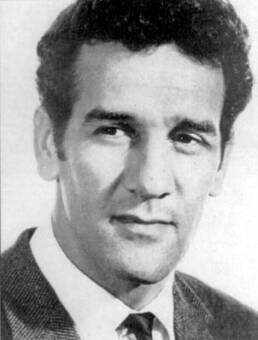

Aboriginal Australian professional soccer player, activist and public servant, Charlie Perkins (1936-2000), was in institutions from the age of ten.

Charlie Perkins was born at an institution for Aboriginal children, The Bungalow, in Alice Springs in the Northern Territory. His mother was Hetti Perkins, an Arrente woman, and his father was Martin Connelly, a Kalkadoon/Irish man.

At the age of ten, Charlie was separated from his mother and taken to live in Adelaide, South Australia at St Francis House with Gordon Briscoe and other Aboriginal boys.

Not keen on school, Charlie excelled at soccer and he played professionally for the English team, Everton, in 1957.

Despite an offer to trial with Manchester United in the English first division, Perkins returned to play for South Australian second division side Croatia. Immediately he led Croatia to promotion to the first division in 1959 and a victory in the Advertiser Cup in 1960 (Gorman).

Charlie couldn’t help but notice the disparity; amongst soccer players—many of whom were recent migrants to Australia—he was treated as an equal, yet as an Aboriginal Australian he “didn’t have the chance to vote” and Aboriginal Australians “were still second-class citizens in those days” (Gorman).

While he was in England and despite his poor academic results in high school, Charlie Perkins was motivated to improve his formal education. In 1965 he became one of only two Aboriginal students to attend Sydney University (and he was one of the first Aboriginal students to graduate) and he was pivotal in forming the Student Action for Aborigines (SAFA) group which organised a Freedom Ride through New South Wales.

About thirty students, led by Perkins, travelled to Walgett, Moree, Kempsey and other towns exposing discrimination in the use of halls, swimming pools, picture theatres and hotels. In a number of towns Aboriginal returned servicemen were only permitted entry to the Returned Service League Clubs on Anzac Day. This trip became known as the Freedom Ride and assumed iconic status as the students ensured that they had press coverage for the conflicts which occurred in this towns (National Museum Australia).

The Freedom Ride marked the beginning of Perkins’ political career. He organised other protests and helped to set up—and he worked for—the Foundation for Aboriginal Affairs in Sydney.

In 1969 Charlie Perkins moved to Canberra and worked for the Commonwealth Office of Aboriginal Affairs. For health reasons, he later transferred to the Adelaide office. From 1984 Perkins was Secretary of the Department of Aboriginal Affairs, but resigned in 1988. Then in 1993 Perkins was elected Commissioner of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (ATSIC) in Alice Springs.

Charlie Perkins was awarded an Order of Australia medal in 1987 for services to the Aboriginal community and was honoured with a state funeral on his death in 2000.

The Charles Perkins Centre at the University of Sydney was established in 2012.

References:

“Charles Perkins.” National Museum Australia. https://www.nma.gov.au/explore/features/indigenous-rights/people/charles-perkins

Gorman, Joe. “Buried history: aboriginal leader Charles Perkins was a pioneering soccer star.” The Sydney Morning Herald, 16 October 2015. https://www.smh.com.au/national/charles-perkins-soccer-star-20151015-gka0by.html

“St Francis House (1946 – 1961).” Find & Connect, 2020. https://www.findandconnect.gov.au/guide/sa/SE00015

“The Bungalow (1914-1942).” Find & Connect, 2019. https://www.findandconnect.gov.au/guide/nt/YE00019

Image available here.