These life stories may contain descriptions of childhood trauma and abuse, as well as images, voices and names of people now deceased. If you need help, you can find contact details for some relevant support services on our support page.

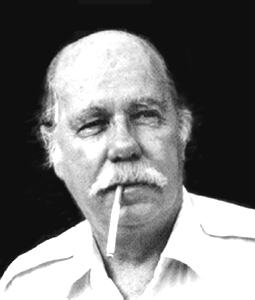

American writer and academic, Charles Willeford (1919-1988), was in kinship care as a child.

Charles Willeford was born in Little Rock in the southern state of Arkansas. His father died when he was two and Charles’ mother moved to California to be with her family. However, she died too when the boy was eight.

“When you’re an orphan at the age of eight, you realize that you’re the next one to die,” he once told an interviewer. “Your vision of life is colored by reality rather than pipe dreams” (Adler).

From then Charles was living with his grandmother, Mattie, in Los Angeles and Mattie sent him to boarding school for a couple of years. After his grandmother lost her job—it was 1932 and the Great Depression was in full swing—the thirteen-year-old, not wanting to burden his grandmother, headed out on his own, living as a road kid.

I wasn’t alone. There were thousands of boys my age riding freight trains to nowhere. But no one can ever tell me I didn’t have a happy childhood (Siegel).

Charles joined the army at the age of sixteen where he stayed until 1956. He was awarded the Purple Heart during the Battle of the Bulge. He published his first book, a book of poetry entitled Proletarian Laughter, when he was serving in the military and his “first great work, The Woman Chaser, was published in 1960” (Siegel).

It’s a novel structured as a screenplay about a used car salesman, Richard Hudson…Hudson is both an average middle-class climber and violent narcissist gripped by a spasm of artistic vision for which he’s willing to sacrifice everything. It’s a beautifully strange book and shows Willeford, for the first time, in full control his powers as a writer (Siegel).

In the years after his military career, Charles Willeford obtained both bachelor’s and masters’ degree from the University of Miami. He subsequently taught creative writing at Miami-Dade Community College, reviewed books for The Miami Herald for 20 years, inspired Quentin Tarantino, and wrote books.

Four of Willeford’s books have been adapted as films: Cockfighter (1974); Miami Blues (1990); The Woman Chaser (1999); and The Burnt Orange Heresy (2019).

Charles Willeford belongs, writes Jacob Siegel:

…to a certain school of American writers, truants really…outsiders, not in the high-art sense of a cultivated avant garde, but in the practical sense—they had chops and insights but no gate into the literary club and no intention of doing a soft shoe to get in.

References:

Adler, Dick. “Poet of Noir.” Chicago Tribune, 15 March 1998. https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/ct-xpm-1998-03-15-9803150130-story.html

Fisher, Marshall. The Unlikely Father of Miami Crime Fiction. The Atlantic, May 2000. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2000/05/the-unlikely-father-of-miami-crime-fiction/305143/

Herron, Don. “Collecting Charles Willeford.” Don Herron Website. https://donherron.com/some-essays/collecting-charles-willeford/

Siegel, Jacob. “The Train-Hopping, Nazi-Fighting Literary Hero You’ve Never Heard Of.” Daily Beast, 11 November 2015. https://www.thedailybeast.com/the-train-hopping-nazi-fighting-literary-hero-youve-never-heard-of

Image available here.