These life stories may contain descriptions of childhood trauma and abuse, as well as images, voices and names of people now deceased. If you need help, you can find contact details relevant support services on our support page.

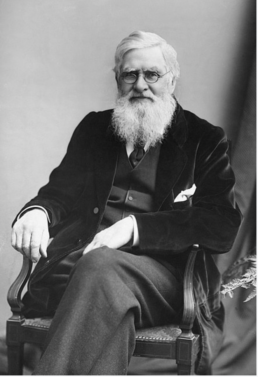

British evolutionary scientist and writer, Alfred Russel Wallace (1823-1913), was in foster and kinship care as a child.

Alfred was born in the town of Usk in Monmoutshire, Wales. He was the eighth of nine children born to Mary Anne Greenell and Thomas Vere Wallace.

Although Thomas and Mary Anne came from the middle class and had many relatives who were lawyers, Thomas was unsuccessful at his various ventures. Therefore, the family struggled economically. The Wallaces could only afford a “lower-grade grammar school training” for Alfred. He attended Hertford Grammar School for seven years which was the extent of his formal education.

But the Wallace household was rich in culture. His father belonged to reading clubs and borrowed from libraries and the boy was free to “tinker”. Wallace regarded his home life as “more educational” than the time he spent in school.

Alfred and his older brother, John, who was about five years older were “constant companions.” The two boys occupied themselves making fireworks, gunpowder, toys, pop guns and other weapons. After John left home to take up an apprenticeship as a carpenter, Alfred spent more time reading.

Alfred’s first experience away from his family was around the age of ten.

…for some family reason that I quite forget, I was left to board with Miss Davies at All Saints’ Vicarage, then used as a post-office, a large rambling old house with a large garden, in which there was among other fruit an apple tree… (Wallace, p. 70).

It is unknown as to how long Wallace was in foster care with Miss Davies. He also boarded for some months at his school. At the time, his family was going through a number of challenges including the death of a daughter and further financial difficulties.

In 1837 at the age of fourteen, Alfred was sent to London to live with his nineteen-year-old brother who was an apprentice carpenter. Alfred lived with him for about six months until their eldest brother, William, could employ Alfred as an apprentice surveyor.

As I shared my brother’s bedroom and bed, I was no trouble, and I suppose I was boarded at a very low rate (Wallace, p. 79).

During the day Alfred had nothing to do.

…I used to spend the greater part of my time in the shop, seeing the men work, doing little jobs occasionally, and listening to their conversation…I soon became quite at home in the shop and got to know the peculiarities of each of the men…(Wallace, p. 80).

In the evenings, John took his brother along to the “Hall of Science.”

… a kind of club or mechanics’ institute for advanced thinkers among workmen, and especially for the followers of Robert Owen, the founder of the Socialist movement in England (Wallace, p. 87).

During the 1840s, Alfred undertook many jobs in order to support himself. Then, in 1848 he left England for a trip to the Amazon with Henry Walter Bates, a naturalist and explorer. The pair collected specimens of insects and animals, making the trip a financial success.

This marked the beginning of Alfred’s extensive travels. He wrote about some of these trips in The Malay Archipelago, which was first published in 1869. It is considered one of “the most celebrated of all travel writings on this region, and ranks with a few other works as one of the best scientific travel books of the nineteenth century,” (Beccaloni & Smith).

Alfred went on to become a significant scientist. He jointly published on the theory of evolution with Charles Darwin in 1858. However, the following year, Darwin’s On the Origin of Species (1859) “truly grabbed the public’s imagination”, positioning him as the sole originator of natural selection.

Alfred Wallace was nonetheless highly regarded as a great scientist of his time, and arguably “as well known and nearly as influential as Darwin”. He received “honorary doctorates from the University of Dublin in 1882 and Oxford University in 1889”. There is a commemorative plaque in his honour in Westminster Abbey next to Darwin’s.

Alfred was a member of Britain’s “major scientific societies, including the Royal Society”. He wrote on a wide range of specialised scientific topics and published twenty-two books. His five hundred and eight scientific papers were published in the top academic journals of his time, including thirty-eight percent in Nature.

Alfred received many honours for his contributions to biology, geography, geology and anthropology. Some of these include the Royal Geographical Society Founder’s Medal and an Order of Merit, “the highest honour that could be given by the British monarch to a civilian” (Beccaloni & Smith).

Alfred died in his sleep at the age of ninety-one on 7 November 1913. He was survived by his wife, Annie Mitton, and two of their three children.

Although Charles Darwin is likely to forever be associated with evolutionary theory, there have been efforts in recent years to recognise the contributions of Alfred Russel Wallace.

References:

Beccaloni, George, & Smith, Charles. (2015). “Biography of Wallace.” The Alfred Wallace Website. https://wallacefund.myspecies.info/content/biography-wallace

Leonard, Kevin. (2013). “Why does Charles Darwin eclipse Alfred Russel Wallace?” BBC News, 26 February 2013. https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-wales-21549079

Shermer, Michael. (2002). In Darwin’s shadow: the life and science of Alfred Russel Wallace. Oxford University Press.

Wallace, Alfred Russel. (1905). My Life. A Record of Events and Opinions. London: George Bell & Sons.

Image available here.