These stories may contain descriptions of childhood trauma and abuse. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people should be aware that this website may contain images, voices or names of people who may have passed away. If you need help, you can find contact details for some relevant services on our support page.

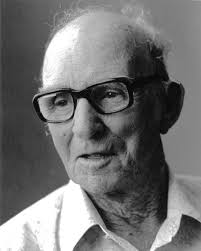

Australian trams man, farmer and writer, Albert Facey (1894-1982), was in kinship care, foster care, and work placements as a child.

Albert Barnett Facey was born in Maidstone, Victoria. Shortly after Albert was born, his father, Joseph, left for the Western Australia goldfields; he died in 1896 without Albert seeing him again.

Joseph Facey had taken two of his four sons with him to Western Australia, Joseph and Vernon. On receiving the news that her husband was dead, Albert’s mother, Mary Ann Facey, left the remaining five children with their maternal grandparents in Barker’s Creek, near Castlemaine, 125km north-west of Melbourne. Mary Ann travelled to WA to retrieve her teenage boys but stayed west, marrying a man for whom she had been working.

In 1898, Albert’s grandfather died and the family, already impoverished, struggled financially. Albert’s brother, Eric, only twelve, left school and went to work and his ten-year-old sister, Laura, left home to help an uncle who had three children.

When his grandmother became ill in 1899, the family was left in considerable financial distress, with only Eric’s wages coming in. Grandmother decided to sell up and move to Western Australia where the family initially moved in with Mary Ann’s sister, Alice, in Kalgoorlie. Two years later, the extended family left Kalgoorlie for land Alice’s husband had bought near Narrogin, 192 KM south-east of Perth.

Albert was eight years of age when he first went out to work. He was asked to be a companion for a man’s mother when the man was out at work.

I soon found that my job wasn’t going to be light. In fact, I had to keep going from daylight to dark. Many times I wished I was back with Uncle, the kids and dear old Grandma (Facey p. 14).

Albert wasn’t paid for his work and he was soon dressed in rags so nine-year-old Albert decided to run away. He made it back to his uncle’s house where he lived until he was eleven and was offered another job to look after poultry. Again, he wasn’t paid and again he returned to his uncle’s house.

Albert’s next work placement was with a couple called Philips, where he was very happy until the Philips wanted to adopt Albert and his mother refused to allow that.

Thirteen-year-old Albert left the Philips and moved in with the Bibby’s who treated the boy well.

At age fourteen, Albert decided to visit his mother, who was now living in Subiaco, Perth with her husband and three children from her second marriage. Eric was told he’d need to get a job and pay board as the family couldn’t afford to send him to school. After a few weeks living with his mother and doing odd jobs, Albert left for Geraldton, 424 km north of Perth, to take up work mustering cattle.

Albert Facey continued this pattern of moving around to do an assortment of labouring and farming jobs until he signed up for the army in 1914 and left for Cairo in February 1915. He arrived back in Western Australia at the end of that year after sustaining an injury.

About one hundred of us were taken straight to the No. 8 Australian Military Hospital at Fremantle. I was ordered to bed and remained there through Christmas time. Late in January I was allowed to get up. My right leg, which was severely crushed in the blast, never really recovered and walking was difficult. I was allowed out on daily leave on the condition that I move slowly and keep away from crowds (Facey p. 145).

Shortly after his return to Australia, Albert met his wife-to-be, Evelyn Gibson. The couple married in 1916, the same year Albert qualified to work as a conductor for Perth Tramways. Evelyn and Albert also had a couple of attempts at farming, their most successful being a poultry farm they ran from 1947. They then successfully flipped land until in 1958, sixty-four-year-old Albert retired.

During the 1970s, and encouraged by his family (Albert and Evelyn had seven children between 1919 and 1939, the oldest of whom died serving in WWII), Facey—who had taught himself to read and write—began to write down the many stories he had told over the years.

Says his grandson, John Rose:

When he finally finished writing his story, we thought we’d have a few copies printed for members of the family. We approached Fremantle Arts Centre Press and asked them to produce thirty copies for us. However, they insisted on publishing the book at their expense and selling it through the bookshops.

Albert Facey died only nine months after his book, A Fortunate Life, was published to wide acclaim. It is now recognised as an Australian classic and has been adapted for television and the stage.

References:

Facey, A.B. A Fortunate Life. Melbourne: Puffin Books, 1981

Image available here.